Water is a molecule

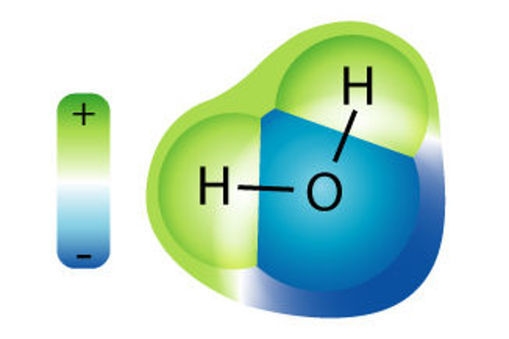

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms that bond or ‘stick’ together. Water is a molecule. It is made up of two hydrogen (H) atoms and one oxygen (O) atom that are chemically bonded together. The H and O are symbols for the atoms that make up water. This is why people often call water H2O.

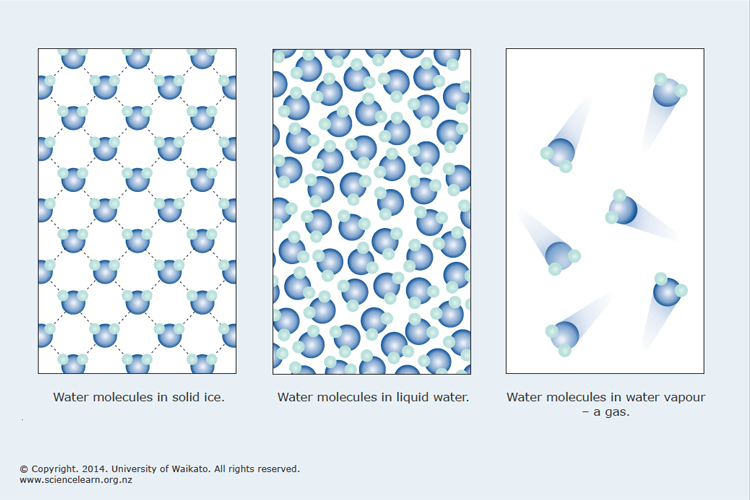

Water can change from a liquid to a solid or a gas and back to a liquid, over and over again. Not all substances can do this as heat can chemically change some molecules, for example if you burn wood the molecules are permanently changed and this change cannot be reversed. This is known as a chemical change.

Physical changes in state do not permanently change the molecules. If you change the state of water you don't change the amount of water or the molecules that make up this water. A water molecule is always H2O whether it is liquid water, ice or water vapour. The only thing that changes is the movement of the water molecules:

- Water molecules in ice are stationary

- Water molecules in a liquid move slowly

- Water molecules in a gas move quickly

Where we find water

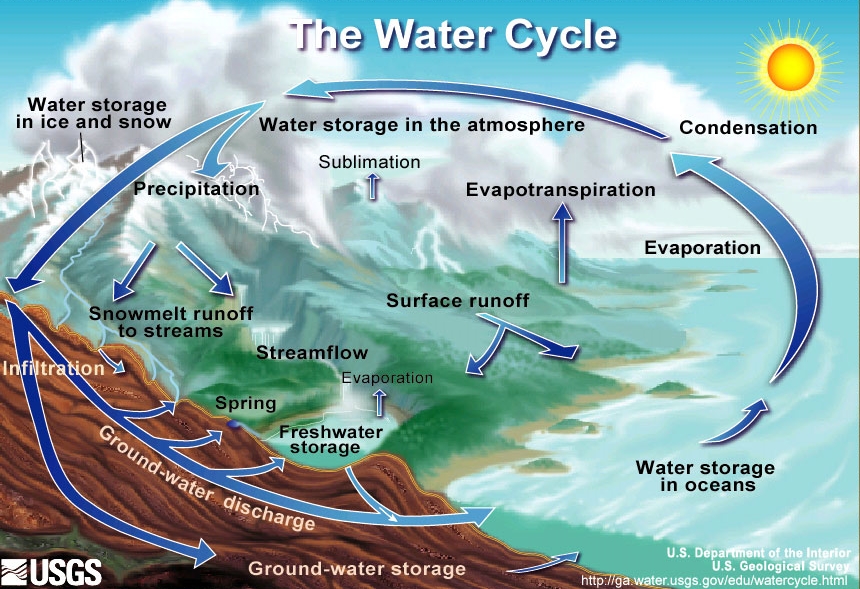

Rivers, groundwater, lakes, oceans and rain represent the liquid state of water.

In its gaseous state, water vapour is evaporated by the sun’s solar radiation from the surface of water bodies like oceans or lakes, and from the surface of plants and the land. Water vapour can also evaporate directly from its frozen state.

Snow and ice represent the solid form of water. They can be found in the Earth’s polar icecaps and on top of high mountains. Some of the snow and ice melts and turns into liquid water. In the polar regions, ice can stay frozen for thousands of years.

Only a very small amount of the total amount of water (about 0.3%) is drinkable water.

Water’s journey

If you leave some water on a saucer by a window, it will eventually evaporate. This happens only if there is enough thermal (heat) energy available for the water molecule to vibrate so much that the molecules ‘break’ out of their liquid structure and turn into a gas.

But why do the oceans not dry up? In fact, most evaporation occurs from ocean water, but much of the evaporated water rains back into the oceans again. Some falls on the land surface and might spend some time there as ice, snow, groundwater or in streams, or it may be stored in lakes before it returns back to sea.

This journey is called the hydrological cycle or water cycle. It describes the exchange of water in every form between the Earth’s systems and is part of what makes the Earth so unique. Understanding things that can affect the water cycle helps us to understand how climate change will affect people. This cycle is complex and small changes in things like temperature can cause large changes in the whole system.

Where Wellington’s water comes from

The Wellington region has three sources of drinking water:

- The Hutt River

- The combined flow of the Wainuiomata and Orongorongo Rivers

- The Waiwhetu Aquifer - a natural underground reservoir beneath the Hutt Valley that is fed by river-water seeping into the ground.

Wellington Water manages these water sources to protect the quality of the water collected from them. The river water collection areas are in mountainous land upstream of human settlement. Public access to them is limited to minimise the risk of human contamination.

River water will have some natural contamination in it, from dirt, decaying vegetation and animal waste. Microbiological contamination from animals can cause serious illness in people, so Wellington Water monitors animal numbers closely in the water collection areas. Pest animal control is undertaken when needed.

River and aquifer water also absorbs chemical elements from the land that it flows over and through. Some of these elements can be harmful to humans if consumed at high levels. Wellington Water monitors the levels of several naturally occurring chemical elements in our water to ensure it’ll be safe to drink.